“Masonry, like all the Religions, all the Mysteries, Hermeticism, and Alchemy, conceals its secrets from all except the Adepts and Sages, or the Elect, and uses false explanations and misinterpretations of its symbols to mislead those who deserve only to be misled, to conceal the Truth, which it calls Light, from them, and to draw them away from it.”

Albert Pike, former Sovereign Grand Commander

The Masonic infiltration which has penetrated very deeply into the heart of the Church is often reflected in the layout of modern churches. The designs which reveal Masonic influence track closely with the liturgical changes that took place after the Council, and which were first exposed by Cardinals Ottaviani and Bacci in their historic Intervention. Their letter to Pope Paul VI, and its attached document compiled by a group of theologians, became known as the Ottaviani Intervention.That document lists the main problems detected in Pope Paul’s New Order of the Mass:

- definition of the Mass (supper, memorial, assembly instead of Sacrifice)

- purpose of the Mass (community/fraternal charity instead of Sacrifice and worship)

- essence of the Mass (thanksgiving – actually a fruit instead of the Mystery of Calvary continued)

With regard to liturgical design, these changes were achieved by

- reducing the main altar to a table

- eliminating the sanctuary and placing the altar in the midst of the people

- omitting specifically Catholic elements

- inverting the roles of priest and laity

- eliminating hierarchical structure

- implicitly denying the Real Presence

- having the priest face the people to support the idea of narrative rather than sacrifice

- providing limitless options to undermine unity

- using ambiguous designs and art

- focussing on ‘paschalism’ to the exclusion of other communications of grace

- promoting “archaeologism”, condemned by Pope Pius XII, to suggest that the Church has somehow lost Her way in more recent times.

It is easy to see how these novel elements in design are closely aligned with Masonic principles of liberty, equality and fraternity.

Traditionally, the design of a church symbolises the exclusive and hierarchical nature of Catholicism. The Sacrifice of the Mass takes place in a dedicated area, the Sanctuary, which is only entered by males. Only an ordained priest may offer the Mass, and steps surrounding the altar denote his ascent on behalf of the people towards the Triune God.

By contrast, the egalitarianism of Masonry sees the altar moved to the midst of the people, with the priest mingling among them. Steps no longer appear, and on some churches, the altar is even placed at a lower level than the congregation.

Specifically Catholic elements such as statuary, side altars, traditional motifs in stained glass windows, artwork and textiles point to a Church which believes Herself to be the One True Faith. These must be jettisoned in favour of the more universal “spiritualism” found in Masonry.

In line with the Masonic need for secrecy and misdirection, ambiguous patterns and symbols create confusion, replacing clear catechesis with mystical suggestions. In accordance with the Masonic principle of liberty, these creative details invite the designer or congregation to express their individuality, rather than being subservient to traditional themes and motifs.

The principle of fraternity is expressed when a church’s design emphasises a merely human charity – an assembly of people gathered to pray for the poor or to build up the their community. Any reference to the Mass as a Sacrifice, or focus on the Real Presence of the Lord in the tabernacle is eliminated. Similarly, artwork reminding parishioners of their eternal destination is replaced by representations of the corporal works of mercy.

Some specific examples of these principles are found in the churches shown below.

Saints Peter and Paul, in Bulimba, Brisbane. [Queensland, Australia.]

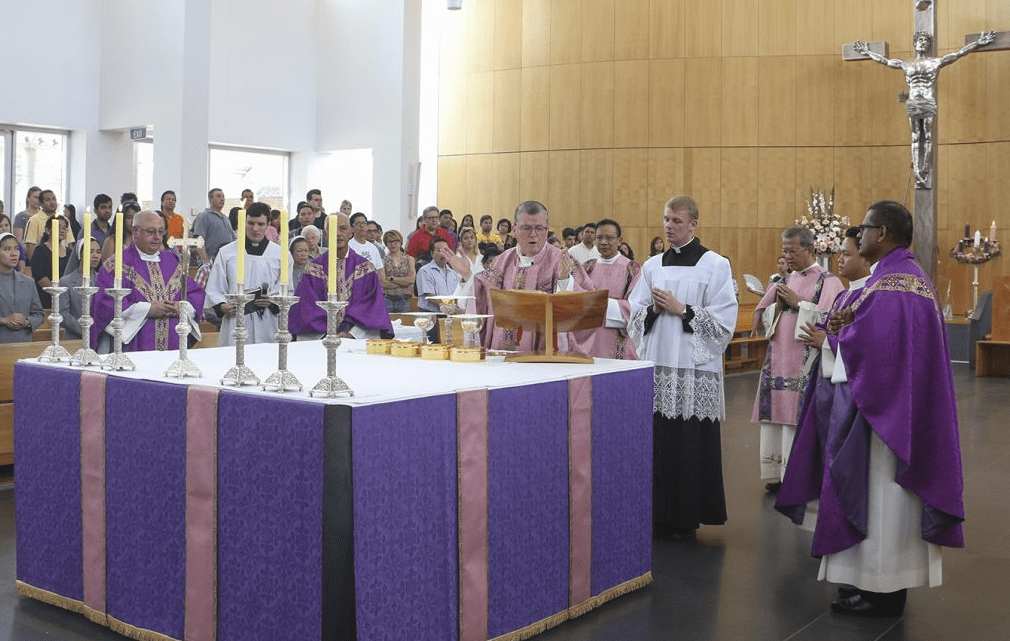

As explained in notes about the church’s interior found on the parish website, this layout represents the theology wherein the assembly, that is the congregation, is the celebrant of the liturgy. Thus the priest loses his preeminent place and merges with the people. This was one of the concerns raised in The Ottaviani Intervention and represents the Masonic principle of egalitarianism.

Focus on the priest , as a man, actually increases in this layout and the people are forced to stare at each other.

According to the notes, both the altar and the ambo are cubes, each carved from a single block of marble and decorated with arches. Notably, the Le Guide du Paris Maçonnique, explains that the perfect cube, the cut stone and the arches are all “inherently Masonic.” [As related in Unholy Craft: Freemasonry and the Roots of Christophobia.]

As an aside, the priest in question held, as a fundraiser for the Church’s renovations, a Black and White Ball. It is a small point but interesting in the context of this discussion.

Another example of a cube-shaped altar can be found in this German church. Made of red marble, the altar was consecrated by Auxiliary Bishop of Munich, Rupert Graf zu Stolberg, at the St. Michael Church in Niederaudorf.

St. Patrick’s at Parramatta, Sydney. [New South Wales, Australia.]

This rather sparsely-decorated cathedral has been described by visitors as a ‘barn’ or a ‘basketball court’. The shift from Catholic, theocentric liturgical design to a Masonic, anthropocentric one is very clear here: there is no tabernacle in the main body of the church, and the lectern faces over the altar to the crucifix on the back wall. What looks like a floating storm cloud, is said by the designer to embody “a sublime narrative of spiritual life.”

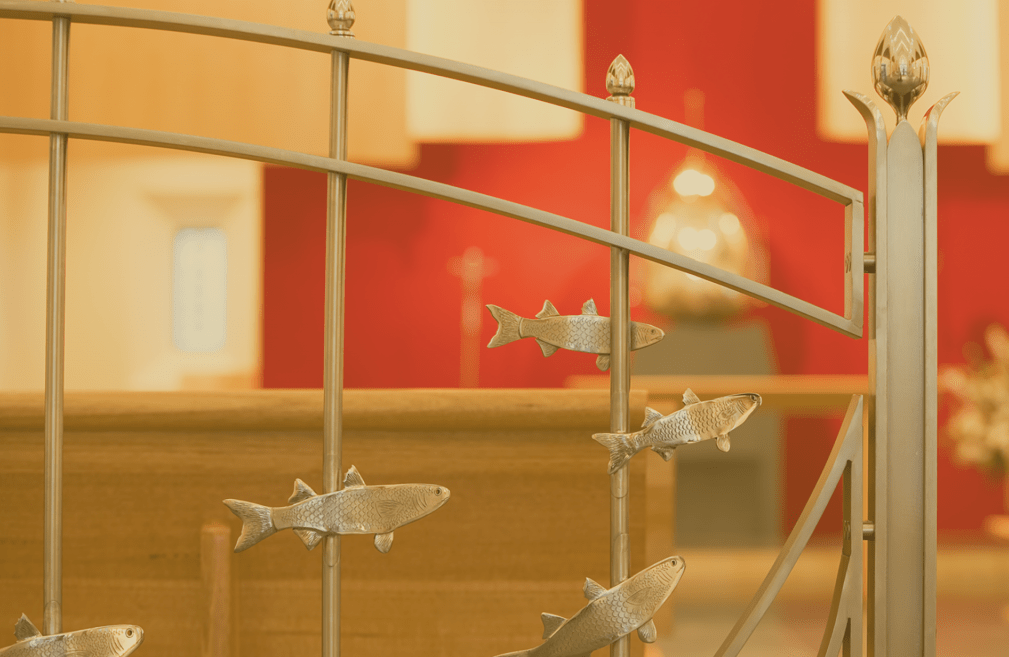

The altar is a very egalitarian square. While not ugly, the fish and decoration shown at the entrance to the Adoration chapel, are ambiguous: they in no way point to the reality of the Real Presence only a few feet away.

The ‘presider’s chair’ is brutalist and situated near a rather grotesque crucifix. Notably, the arms of the cross are incomplete.

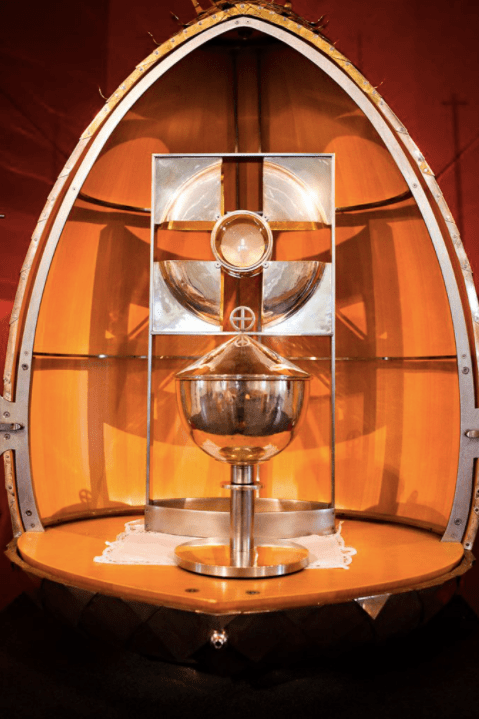

The tabernacle, like its decorations, is quite ambiguous: it is difficult to discern what we are looking at. The arms on the cross surrounding the Sacred Host are of the same length – a common occult representation of a cross which is commonly found in Rosicrucianism.

Banyo Seminary Chapel, Brisbane. [Queensland, Australia.]

Another example is this chapel in a dioscesan seminary in Australia. Again we see the altar and ambo have been brought into the midst of the congregants. No sanctuary, as such, exists. Congregants are left with little choice but to look at each other, instead of being able to gaze unimpeded at the Holy Sacrifice unfolding before them.

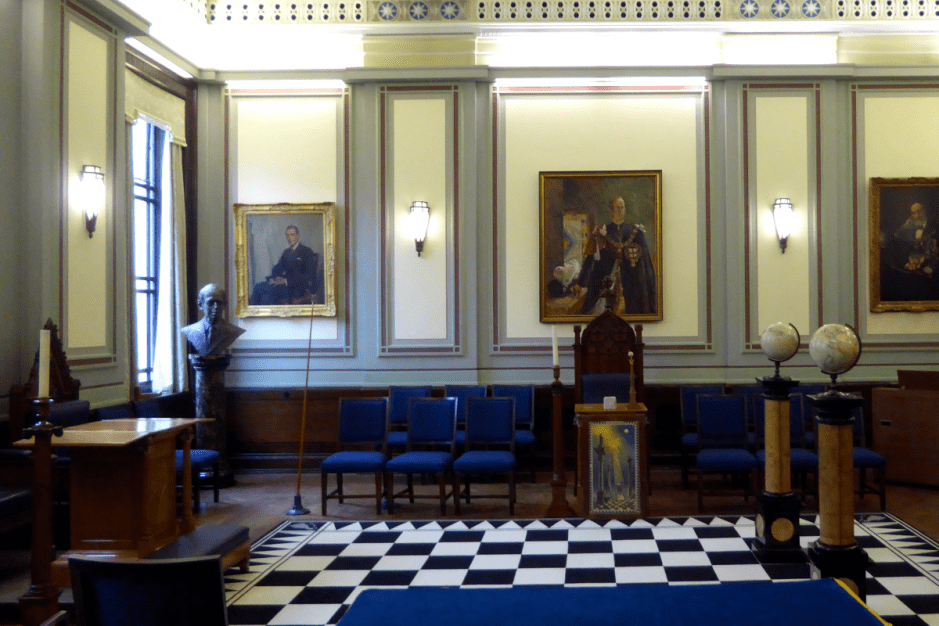

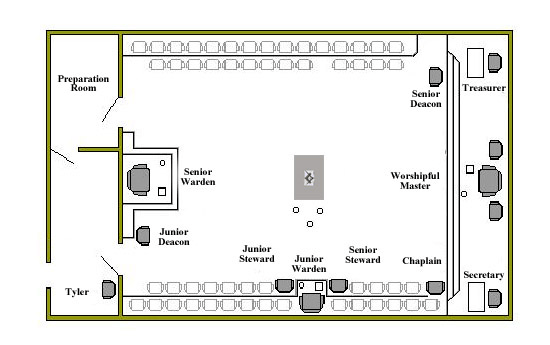

If we compare the three new churches above to the typical layout of a Masonic temple, we are at once struck by some obvious similarities. In the lodge, chairs are arranged in rows with the people facing each other. A table, known as the Table of the Book, is situated between the rows of chairs. In this layout, the focus is on man, which is a fundamental problem in new church designs as well.

Where once the focus of the Mass was clearly on God – as the faithful, along with the priest, faced the high altar with tabernacle and a prominent crucifix – these modern designs place the emphasis firmly on man. This novelty takes on a more sinister aspect with the introduction of occult-inspired details, such as the cube-shaped altar. In that case, what could be put down to mere ideological influence is clearly exposed as an attempt to replace the object of worship: Christ for Antichrist.